According to the U.S. Department of Justice, American Indian women are 2½ times more likely to be sexually assaulted than other women.

A report issued three years ago by the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center interviewed women and girls who had been sexually trafficked, and found that many assumed being pimped out by their boyfriends was just a normal part of life.

More than 60 percent of perpetrators of domestic violence on Indian reservations are non-Indian, according to the Justice Department.

These are issues close to the hearts of author Louise Erdrich and activist Winona LaDuke, two of the best-known Indian names in Minnesota. Next Tuesday, they will join playwright Eve Ensler at an Honor the Earth benefit. Ensler, best known for her popular play “The Vagina Monologues,” has raised millions of dollars for women’s causes worldwide.

At the fundraiser, which also includes a performance by Minneapolissinger Chastity Brown, Erdrich and LaDuke will discuss a specific type of trouble spot where such violence is even more likely to occur — oil boom towns like those that have popped up in North Dakota.

There is a link between abuse of women and the extreme extraction of fossil fuels, Erdrich said: “Why is it that sex trafficking is part of oil boom town life? Why are Native women particularly vulnerable?”

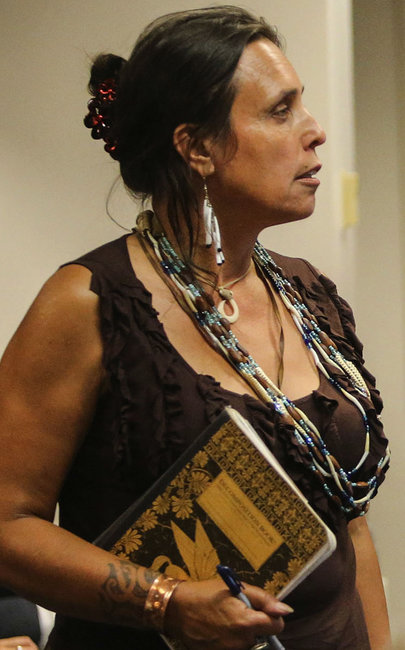

LaDuke, who 20 years ago cofounded the environment-focused Honor the Earth with the musical duo Indigo Girls, said that while poverty, substance abuse and related risks plague other cultures, as well, the traumas and mistrust built up over more than a century of subjugation make these women uniquely susceptible to victimization.

“Native women have historically been the victims of a lot of rape during all the war,” LaDuke said. “It’s the colonization that distinguishes their situation [from other at-risk groups]. They were forced to go from being the harvesters at the center of their own cultures to being outcasts on the margins.”

A past co-chair of the Indigenous Women’s Network, LaDuke noted the compliant imagery associated with American Indian women: “Ask people to name important Native women, and you’ll most often hear Pocahontas and Sacagawea — two women who helped white guys.”

She also pointed to the continentwide pattern of land-based peoples watching their territories overrun by industrial encroachment.

“Whether it’s the gold mining in Northern California or military bases or the Alaskan oil boom and now North Dakota, nine-tenths of the people coming to take the land and water and resources are men, some with criminal histories. And the women and children who live there are the most vulnerable.”

Adding to that vulnerability, LaDuke said, is that non-Indian abusers whose crimes occur on reservations know they are more likely to avoid legal punishment, because tribal leaders lack the authority to prosecute them.

Erdrich said she also wants to address the impact that fracking, tar sands and pipelines like the proposed Sandpiper project in North Dakota have on human health as well as tribal lands.

“Is there a relationship between the violence we are doing to the Earth, and the violence Native women suffer?” she said. “Our conversations will illuminate that connection.”